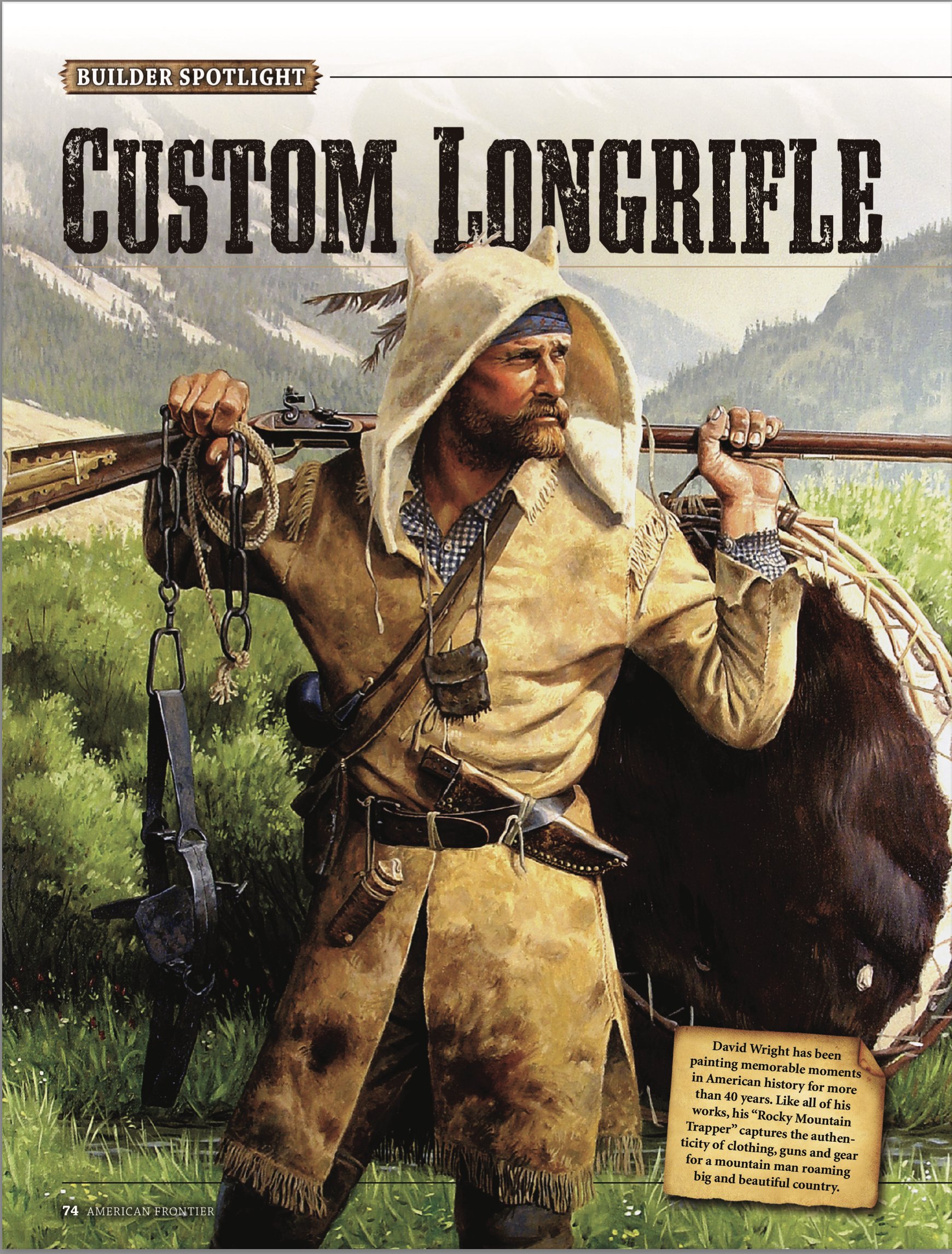

Custom Longrifle Masterpiece

Shawn Webster moonlighted from quill working to build this custom longrifle for the author.

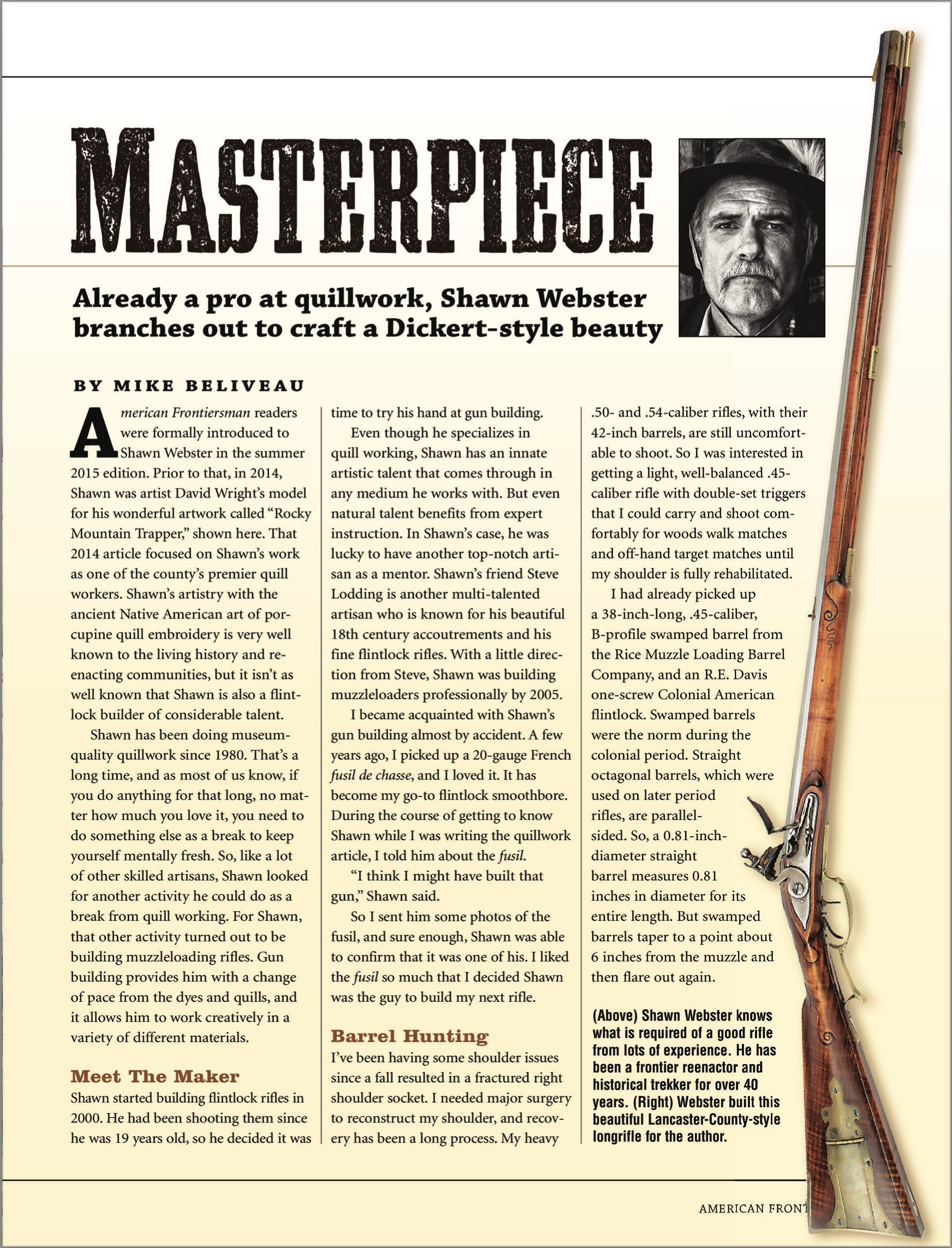

In a previous issue I was able to introduce Shawn Webster to “American Frontiersman” readers. That article focused on Shawn’s work as one of the county’s premier quill workers. Shawn’s artistry with the ancient native American art of porcupine quill embroidery is very well known to the living history and re-enacting communities, but it isn’t as well known that Shawn is also a flintlock gun builder of considerable talent.

Shawn has been doing museum quality quillwork since 1980. That’s a long time, and as most of us know, if you do anything for that long, no matter how much you love it, you need to do something else as a break to keep yourself mentally fresh. So, like a lot of other skilled artisans, Shawn looked for another activity he could do as a break from quill working. For Shawn, that other activity turned out to be building muzzleloading rifles. Gun building provides him with a change of pace from the dyes and quills, and it allows him to work creatively in a variety of different materials.

Shawn started building flintlock rifles in 2000. He had been shooting them since he was 19 years old, so he decided he it was time to try his hand at gun building.

Even though he specializes in quill working, like other talented artisans, Shawn has an innate artistic talent that comes through in any medium he works with. But even natural talent benefits from expert instruction. In Shawn’s case, he was lucky to have another top-notch artisan as a mentor. Shawn’s friend Steve Lodding is another multi-talented artisan, who is known for his beautiful eighteenth century accouterments, and for his fine flintlock rifles. With a little direction from Steve, Shawn was building muzzleloaders professionally by 2005.

I became acquainted with Shawn’s gun building almost by accident. A few years ago I picked up a 20 gauge, French fusil de chasse, and I loved it. It has become my go-to flintlock smoothbore. During the course of getting to know Shawn while I was writing the quillwork article, I told him about the fusil.

“I think I might have built that gun,” Shawn said.

So I sent him some photos of the fusil, and sure enough, Shawn was able to confirm that it was one of his. I liked the fusil so much that I decided Shawn was the guy to build my next rifle.

I’ve been having some shoulder issues since a fall resulted in a fractured right shoulder socket. I needed major surgery to reconstruct my shoulder, and recovery has been a long process. My heavy .50 and .54 caliber rifles, with their 42-inch barrels are still uncomfortable to shoot. So I was interested in getting a light, well-balanced .45 caliber rifle with double set triggers that I could carry and shoot comfortably for woods walk matches and off hand target matches until my shoulder is fully rehabilitated.

I had already picked up a 38-inch long, .45 caliber, B-profile swamped barrel from the Rice Barrel Company, and an R.E. Davis, one-screw Colonial American Flintlock. Swamped barrels were the norm during the colonial period. Straight octagon barrels, which were used on later period rifles, are parallel sided. So, a 13/16th-inch straight barrel measures 13/16ths inches in diameter for its entire length. But swamped barrels taper to a point about six inches from the muzzle and then flare out again.

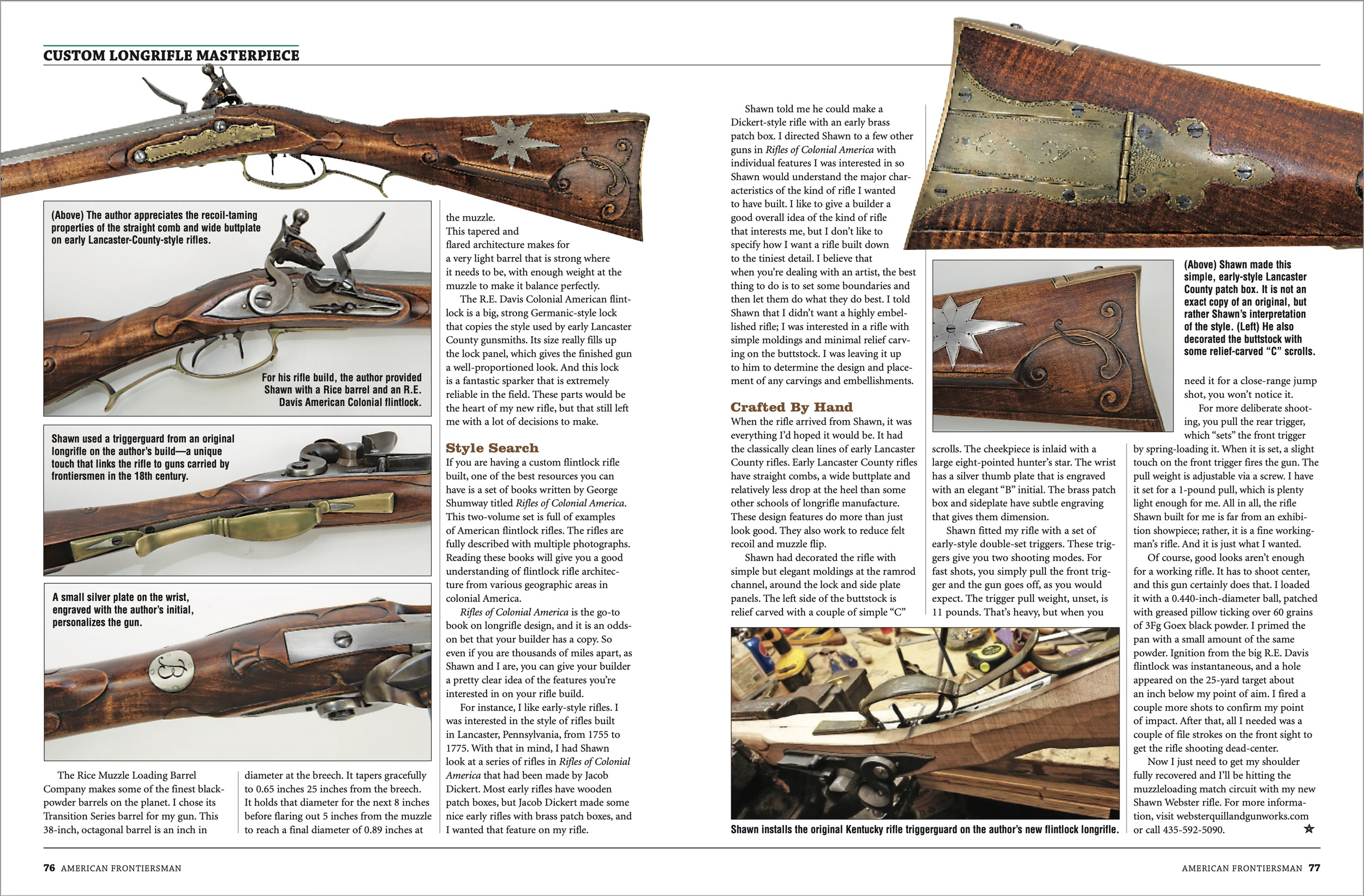

The Rice Muzzleloading Barrel Company makes some of the finest black powder barrels on the planet. I chose their Transition Series barrel for my gun. This 38-inch, octagon barrel is an inch in diameter at the breech. It tapers gracefully to 0.647 inches 25 inches from the breech. It holds that diameter for the next eight inches before flaring out five inches from the muzzle to reach a final diameter of 0.895 at the muzzle. This tapered and flared architecture make a very light barrel that is strong where it needs to be, with enough weight at the muzzle to make it balance perfectly.

The R. E. Davis Company Colonial American flintlock is a big, strong Germanic styled lock that copies the style used by early Lancaster County gunsmiths. It’s size rally fills up the lock panel, which gives the finished gun a well-proportioned look. And this lock is a fantastic sparker that is extremely reliable in the field.

These parts would be the heart of my new rifle, but that still left me with a lot of decisions to make.

If you are having a custom flintlock rifle built, one of the best resources you can have is a set of books written by George Shumway, titled “Rifles of Colonial America”. This two-volume set is full of examples of American flintlock rifles. The rifles are fully described with multiple photographs. Reading these books will give you a good understanding of flintlock rifle architecture from various geographic areas in colonial America.

“Rifles of Colonial America” or RCA for short, is the go-to book on longrifle design, and it is an odds on bet that your builder has a copy. So, even if you are thousands of miles apart, as Shawn and I are, you can give your builder a pretty clear idea of the features you’re interested in on your rifle build.

For instance, I like early style rifles from the 1755 to 1775 period, and I was interested in the style of rifles built in Lancaster, Pennsylvania during that time frame. With that in mind I had Shawn look at a series of rifles in RCA volume one that had been made Jacob Dickert. Most early rifles have wooden patchboxes, but Jacob Dickert made some nice early rifles with brass patchboxes, and I wanted that feature on my rifle.

Shawn told me he could make a Dickert-style rifle with an early design brass patchbox. I directed Shawn to of a few other rifles in RCA with individual features I was interested in, so Shawn would understand the major characteristics of the kind of rifle I wanted to have built. I like to give a builder a good overall idea of the kind of rifle that interests me, but I don’t like to specify how I want a rifle built, down to the tiniest detail. I believe that when you’re dealing with an artist, the best thing to do is to set some boundaries, and then let them do what they do best. So I told Shawn that I didn’t want a highly embellished rifle. I was interested in a rifle with simple moldings and minimal relief carving on the butt stock, but that I was leaving it up to him to determine the design and placement of any carvings and embellishments.

When the rifle arrived from Shawn, it was everything I’d hoped it would be. It had the classically clean lines of early Lancaster County rifles. Early Lancaster County rifles have straight combs, a wide butt plate, and they have relatively less drop at the heel than some other schools of longrifle manufacture. Those design features do more than just look good. They also work to reduce felt recoil and muzzle flip.

Shawn had decorated the rifle with simple, but elegant, moldings at the ramrod channel, around the lock and side plate panels. The left side of the butt stock is relief carved with a couple of simple “C” scrolls. The cheek piece is inlaid with a large, eight-pointed hunter’s star. The wrist has a silver thumb plate that is engraved with an elegant initial “B”. The brass patchbox and side plate have subtle engraving that gives them dimension.

Shawn fitted my rifle with a set of early style double set triggers. These triggers give you two shooting modes. For fast shots you simply pull the front trigger, and the gun goes off, as you would expect. The trigger pull weight, un-set, is 11 pounds. That’s heavy, but when you need it for a close-range jump shot, you won’t notice it.

For more deliberate shooting, you pull the rear trigger, which “sets” the front trigger by spring loading it. When it is set, a slight touch on the front trigger fires the gun. The pull weight is adjustable via a screw. I have it set for a one-pound trigger pull, which is plenty light enough for me.

All in all, the rifle Shawn built for me is far from an exhibition showpiece, rather, it is a fine working man’s rifle. And it is just what I wanted.

Of course good looks aren’t enough for a working rifle. It has to shoot center, and this gun certainly does that. I loaded it with a .440-inch diameter ball, patched with greased pillow ticking over 60 grains of 3Fg Goex black powder. I primed the pan with a small amount of the same powder. Ignition from the big R.E. Davis flintlock was instantaneous, and a hole appeared on the 25-yard target about an inch below my point of aim. After firing a couple of more shots to confirm my point of impact. After that, all I needed was a couple of file strokes on the front sight to get the rifle shooting dead center.

Now I just need to get my shoulder fully recovered and I’ll be hitting the muzzleloading match circuit with my new Shawn Webster rifle.

Point of Contact:

Shawn Webster

426 E Nichols Cyn Rd

Unit 1304

Cedar City, Utah 84721

(435) 592-5090

websterquillandgunworks.com