.44-40 - Black Powder Reloading

Winchester’s .44-40 cartridge was a game-changer. I doubt that Winchester had any idea of the impact this cartridge would have when they developed it. Its official name was .44 Winchester Center Fire (WCF) cartridge, which leads me to believe that Winchester was following the conventional path. As metallic cartridge weapons took hold following the Civil War, most gun manufacturers developed unique, proprietary cartridges to go with their new firearms. That’s how we ended up with cartridges like the .44 Colt, .38 Long Colt, the .44 Evans, the .44 Merwin Hulbert and a host of other evolutionary dead ends that you won’t find on the shelves of your local gun store today.

The .44-40 broke that mold and became the cartridge of choice for most of the handguns and short action lever guns of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. During that period, I’d guess that more unique brands of firearm were chambered in .44-40 than you could tally for every other suitable cartridge combined. That was the case partly because Winchester sold so many rifles chambered in .44-40 that the round was guaranteed to be stocked on store shelves almost anywhere in the country. However, we can point out that Colt also sold a lot of revolvers chambered in .45 Colt, yet you don’t find many non-Colt handguns chambered for that round.

The fact is that the .44-40 cartridge was quickly recognized by the public as an outstanding round for both handguns and carbines. That in turn led to gun makers recognizing that it made better economic sense for them to chamber their new firearms in .44-40 rather than developing a proprietary cartridge of their own. As a result you’ll find guns chambered in .44-40 made by Colt, Smith & Wesson, Remington, Merwin Hulbert, Marlin…all the big boys. That makes it one of the most authentic cartridge choices for old west re-enactors and cowboy action shooters.

Even though most highly competitive CAS competitors now use guns chambered for the light recoiling .38 special, .45 Colt is still the most prevalent cartridge in use by cowboy shooters. But, I’d contend that .44-40 is a far better choice for CAS competitors who do not want to drop down to .38 special. Unlike the .45 Colt, which performs best with 250-grain bullets, the .44-40 is designed to deliver a high level of intrinsic accuracy with lighter recoiling, 200-grain bullets.

The bottlenecked case makes the .44-40 a more reliable feeder than .45 Colt in every rifle I’ve ever shot it in. And that thin mouthed, bottleneck case allows very little black powder fouling to blow back into the rifle’s action. But that thin case also presents difficulties for reloaders. Because it is a bottlenecked case, there are no carbide dies for .44-40. That means the brass has to be lubricated before sizing. Also the .44-40 has been plagued with inconsistent bore sizes over time. Nineteenth century Winchesters and Colt’s had .427 diameter bores. But most modern guns chambered in .44-40 have .429-inch bores, allowing gun makers to use the same barrels for .44 Special and .44 Magnum rounds as they do for .44-40.

With the notoriously thin brass at the case mouth, and with the oversized bullets needed for modern .44-40 replicas, the biggest problems reloading this round are crushed case mouths and bulged crimps. This can pose real problems for reloaders using a single stage press, but those problems are multiplied when you add reloading speed into the equation. However, if you shoot a lot of .44-40 ammo, you will at some point decide that a progressive press is the way to go.

I faced that issue this year when I decided to give my .44 Spl guns a break from cowboy action shooting in favor of a brace of 1875 Remington Replicas and a ’73 Winchester Sporting Rifle, all chambered in .44-40. I decided to migrate .44-40 production from my sedate single stage press to the Dillon 550B.

Dillon doesn’t make a die set for .44-40, but they do have a caliber conversion kit. These kits consist of a shellplate and locator buttons, which allow the cartridge to be correctly aligned with the toolhead as it rotates through the reloading stations, as well as a powder funnel. The powder funnel also functions as the case mouth expander. In the 550B the powder funnel works with the powder die, only in conjunction with the Dillon powder measure. But, that powder measure is not warranted by Dillon to work with black powder. So if you plan on using a die set where you’ll need to use the Dillon powder die, you’ll need to replace the Dillon 550B powder die body with a Dillon 450 powder die. The 450 powder die will let you load with a scoop and funnel, or, with an optional adaptor, it can hold a mechanical black powder measure like a Hornady Lock-n-Load or a Lyman model 55.

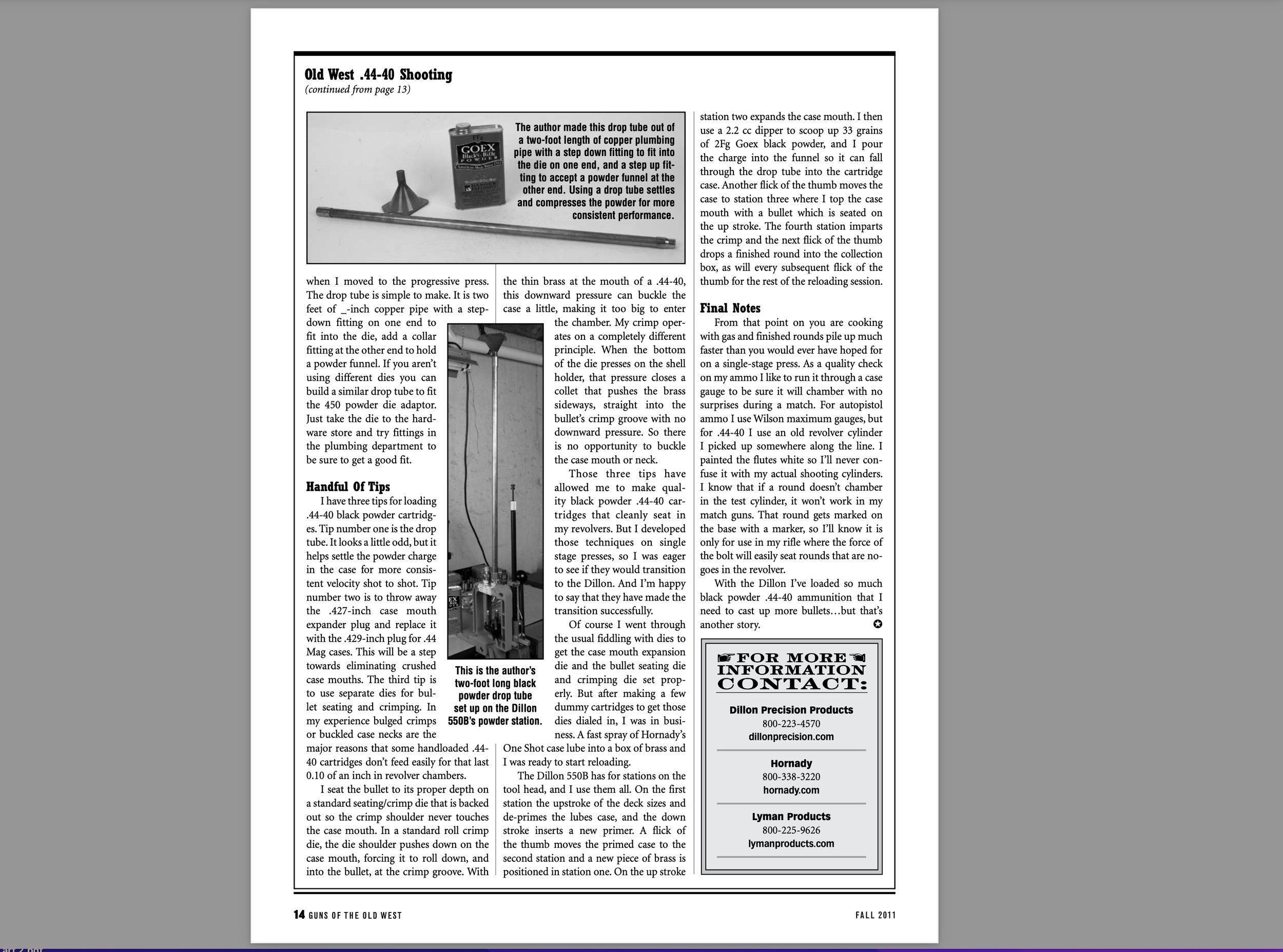

I use a Lee Die set for .44-40 that also loads powder through the powder measure. I had already built a two-foot long powder drop tube, using copper plumbing pipe and fixtures, to fit this Lee powder die on my single stage press, and I didn’t want to lose it when I moved to the progressive press. The drop tube is simple to make. It is two feet of ½-inch copper pipe with a step-down fitting on one end to fit into the Lee powder die, ad a collar fitting at the other end to hold a powder funnel. If you aren’t using Lee dies you can build a similar drop tube to fit the 450 powder die adaptor. Just take the die to the hardware store and try fittings in the plumbing department to be sure to get a good fit.

I have three tips for loading .44-40 black powder cartridges. Tip number one is the drop tube. It looks a little odd, but it helps settle the powder charge in the case for more consistent velocity shot to shot. Tip number two is to throw away the .427-inch case mouth expander plug and replace it with the .429-inch plug for .44 Magnum cases. This will be a step towards eliminating crushed case mouths. The third tip is to use separate dies for bullet seating and crimping. In my experience bulged crimps or buckled case necks are the major reasons that some handloaded .44-40 cartridges don’t feed easily for that last tenth of an inch in revolver chambers.

I seat the bullet to its proper depth on a standard seating/crimp die that is backed out so the crimp shoulder never touches the case mouth. For crimping, I use a Lee Factory Crimp die. In a standard roll crimp die, the die shoulder pushes down on the case mouth, forcing it to roll down, and into the bullet, at the crimp groove. With the thin brass at the mouth of a .44-40, this downward pressure can buckle the case a little, making it too big to enter the chamber. A Lee Factory Crimp Die operates on a completely different principle. When the bottom of the die presses on the shell holder, that pressure closes a collet that pushes the brass sideways, straight into the bullet’s crimp groove with no downward pressure. So there is no opportunity to buckle the case mouth or neck.

Those three tips have allowed me to make quality black powder .44-40 cartridges that cleanly seat in my revolvers. But I developed those techniques on single stage presses, so I was eager to see if they would transition to the Dillon. And I’m happy to say that they have made the transition successfully.

Of course I went through the usual fiddling with dies to get the case mouth expansion die and the bullet seating die and crimping die set properly. But after making a few dummy cartridges to get those dies dialed in, I was in business. A fast spray of Hornady’s One Shot case lube into a box of brass and I was ready to start reloading.

The Dillon 550B has for stations on the tool head, and I use them all. On the first station the upstroke of the deck sizes and de-primes the lubes case, and the down stroke inserts a new primer. A flick of the thumb moves the primed case to the second station and a new piece of brass is positioned in station one. On the up stroke station two expands the case mouth. I then use a 2.2 cc dipper to scoop up 33 grains of 2Fg Goex black powder, and I pour the charge into the funnel so it can fall through the drop tube into the cartridge case. Another flick of the thumb moves the case to station three where I top the case mouth with a bullet which is seated on the up stroke. The fourth station imparts the crimp and the next flick of the thumb drops a finished round into the collection box, as will every subsequent flick of the thumb for the rest of the reloading session.

From that point on you are cooking with gas and finished rounds pile up much faster than you would ever have hoped for on a single stage press. As a quality check on my ammo I like to run it through a case guage to be sure it will chamber with no surprises during a match. For autopistol ammo I use Wilson maximum gauges, but for .44-40 I use an old revolver cylinder I picked up somewhere along the line. I painted the flutes white so I’ll never confuse it with my actual shooting cylinders. I know that if a round doesn’t chamber in the test cylinder, it won’t work in my match guns. That round gets marked on the base with a Sharpie marker, so I’ll know it is only for use in my rifle where the force of the bolt will easily seat rounds that are no-goes in the revolver.

With the Dillon I’ve loaded so much black powder .44-40 ammo that I need to cast up more bullets…but that’s another story.

Points of Contact:

Dillon Precision Products, Inc.

8009 East Dillon's Way

Scottsdale, AZ 85260 U.S.A.

800-223-4570

Lee Precision Inc.

4275 Highway U

Hartford, WI 53027

262-673-3075