Spencer Carbine - From Taylor’s & Co.

The Spencer carbine was the best American cavalry arm of the nineteenth century. That’s my opinion, and I’m sticking to it. The trapdoor Springfield was a fine infantryman’s weapon, but its supposed advantage over the Spencer for mounted troops was largely illusory. The decision to replace the Spencer with the Springfield was an example of the sort of hidebound thinking that plagued the U.S. Army’s ordnance selections for most of the nineteenth century.

If you aren’t familiar with the Spencer it was a seven shot, lever action carbine chambered for the 56-50 rimfire cartridge. It was the most successful cartridge-firing arm of the Civil War. Eventually nearly 100,000 Spencer rifles and carbines were issued to union forces. Spencers were decisive at the battle of Hoover Gap. Colonel Wilder’s mounted infantry. Wilder said after the battle:

“No line of men, who come within fifty yards of another armed with Spencer Repeating Rifles can either get away alive, or reach them with a charge…My men feel as if it is impossible to be whipped, the confidence inspired by these arms added to their terrible destructive capacity, fully quadruples the effectiveness of my command.”

Hoover’s Gap was the first time Spencers were used in combat. They went on to play key roles at Gettysburg, and in defeating General Nathan Bedford Forest in Alabama. Some historians have stated that the Union’s use of Spencer carbines and rifles shortened the Civil War by six months.

After the Civil War, the Spencer carbine moved with the cavalry to the western frontier. The late 1860s was one of the most violent periods on the frontier. In 1866 Red Cloud’s war erupted along the Bozeman Trail in Wyoming, to be followed by General Sheridan’s campaign against the Cheyenne and the Arapaho. The list of battles from this period includes the Fetterman Massacre, Fight, the Battle of Beecher Island and the battle of the Washita. The Spencer rifle featured prominently in these fights.

At Beecher’s Island, Spencers probably meant the difference between a complete massacre, and the command hanging on for three days against immense odds until relief arrived. The battle happened in because Colorado governor Frank Hall asked General Phil Sheridan for help after a series of raids by the Cheyenne and Arapaho left over 70 settlers dead. Sheridan directed Major George Forsyth to raise a force of 50 skilled frontiersmen to operate as a company of mounted scouts. Forsyth armed his men with Spencer carbines, and set off to find the hostiles.

At dawn on the 17th of September, Forsyth, and 48 of his men, were getting ready to break camp when the major spotted the silhouette of a native war bonnet over a ridge. Forsyth grabbed a Spencer carbine and shot the warrior in the head. Almost immediately the general attack commenced. Roman Nose, the Cheyenne war chief launched up to 1,000 southern Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors at Forsyth’s little command. The Indians attacked in a massive wave, but the blistering fire from the four dozen Spencer repeaters broke the charge.

Roman Nose himself was wounded, and died later that night. But, despite the death of their leader, the Cheyenne kept up the fight for five days. When the battle was over the scouts had four men dead on the field, and two more who would die after the battle, as well as another 16 men who were wounded, including Major Forsyth. But their Spencer carbines had inflicted terrible casualties on the Cheyenne, including over 100 warriors killed, many during that first charge.

So, with a battle record like that, you’ve got to wonder why the Spencer was pulled from service. The answer is that it didn’t fit the idea the Ordnance Board had for a military rifle. The Army bureaucracy was very hidebound in their view of weapons. They had a long-standing belief that repeating arms just encouraged soldiers to waste ammunition. This prejudice continued right to the end of the nineteenth century. One big reason the Krag Jorgensen bolt-action rifle was selected as a service rifle in 1893 was because its magazine cut-off, that allowed it to function as a single shot rifle.

The Spencer would never have seen action in the Civil War if it hadn’t been for president Lincoln forcing it on the Army brass. In 1869 the army chief of ordnance admitted that, “The Spencer carbine at the end of the war was generally regarded with favor, and as being the best arm that had been in service, and continues to be regarded as a superior arm by the cavalry.”

But he went on to claim that the single shot Sharps carbine is, “decidedly superior” to the Spencer because it fires the same .50-70 cartridge as the infantry trapdoor rifle of the time. This was just another case of operators valuing combat effectiveness while the brass values low cost and conformity.

Ultimately the ordnance board refused to allow the Spencer carbine into the 1872 trials all, because it could not be modified to fire the .45-70 cartridge. I think that is ironic because, if the .56-50 Spencer had been necked down to .45 caliber, it would have been very comparable to the .45-70 carbine load. The .56-50 Spencer round was loaded with a 350-grain bullet over 45 grains of black powder. Spencer developed a .44 caliber version of his gun for the civilian market. The new cartridge was the 56-46. It loaded a .44 caliber, 320-grain bullet over 45 grains of black powder. Compare that to the .45-70 carbine load with a 405-grain bullet over a 55-grain powder charge. There isn’t much difference in practical performance.

In fact, Custer’s Seventh Cavalry used Spencer carbines in the 1868 Washita campaign. Custer trained his men for over a month at Camp Supply with two target practice drills each day at 100 yards, 200 yards, and 300 yards. The Spencer was very effective out to that range.

I realize that this sort of thing has been the object of speculation for over 100 years, but you’ve got to wonder how Custer would have fared at the Little Big Horn if his men had retained their Spencers. Certainly, if you compare the outcome of Major Forsyth’s 48 men, armed with Spencers fighting off 1,000 Cheyenne at Beecher Island, to Custer’s 210 men armed with single-shot Springfields, who were massacred by 2,000 Sioux at the Little Big Horn, you’ve got to wonder.

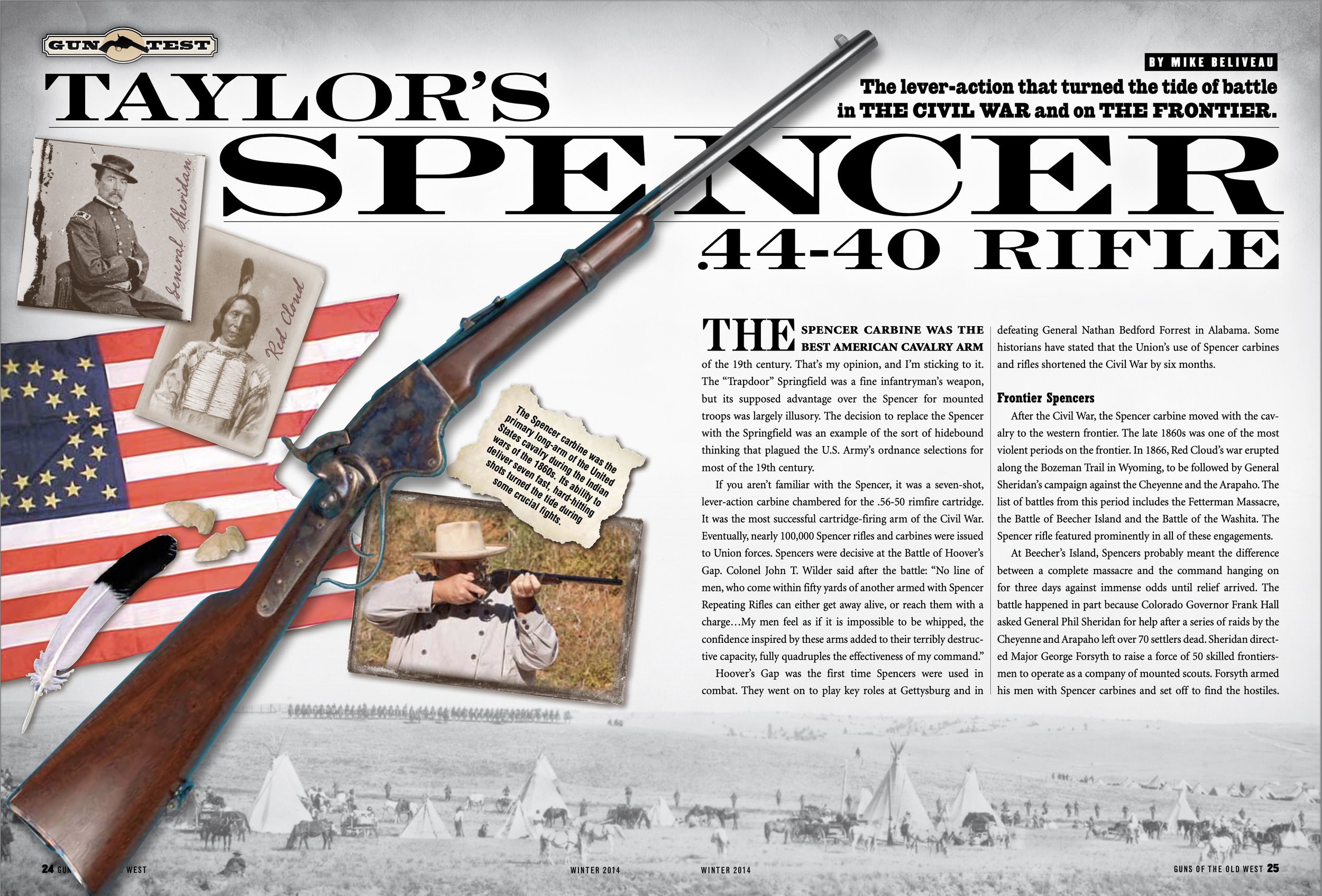

The army’s Ordnance Board may have made a mistake by taking the Spencer carbine out of service, but luckily their decision doesn’t affect you because, thanks to Taylor’s & Company in Winchester, Virginia, you can add a newly manufactured model 1865 Spencer to your personal arsenal. This beautiful recreation is built by Chiappa’s Armi Sport division in Italy, and it looks just the way it should. The forearm and butt stock are made out of a plain grade of quarter-sawn walnut that is stained a rich brown. The discrete satin finish lets the natural warm tone of the walnut take center stage.

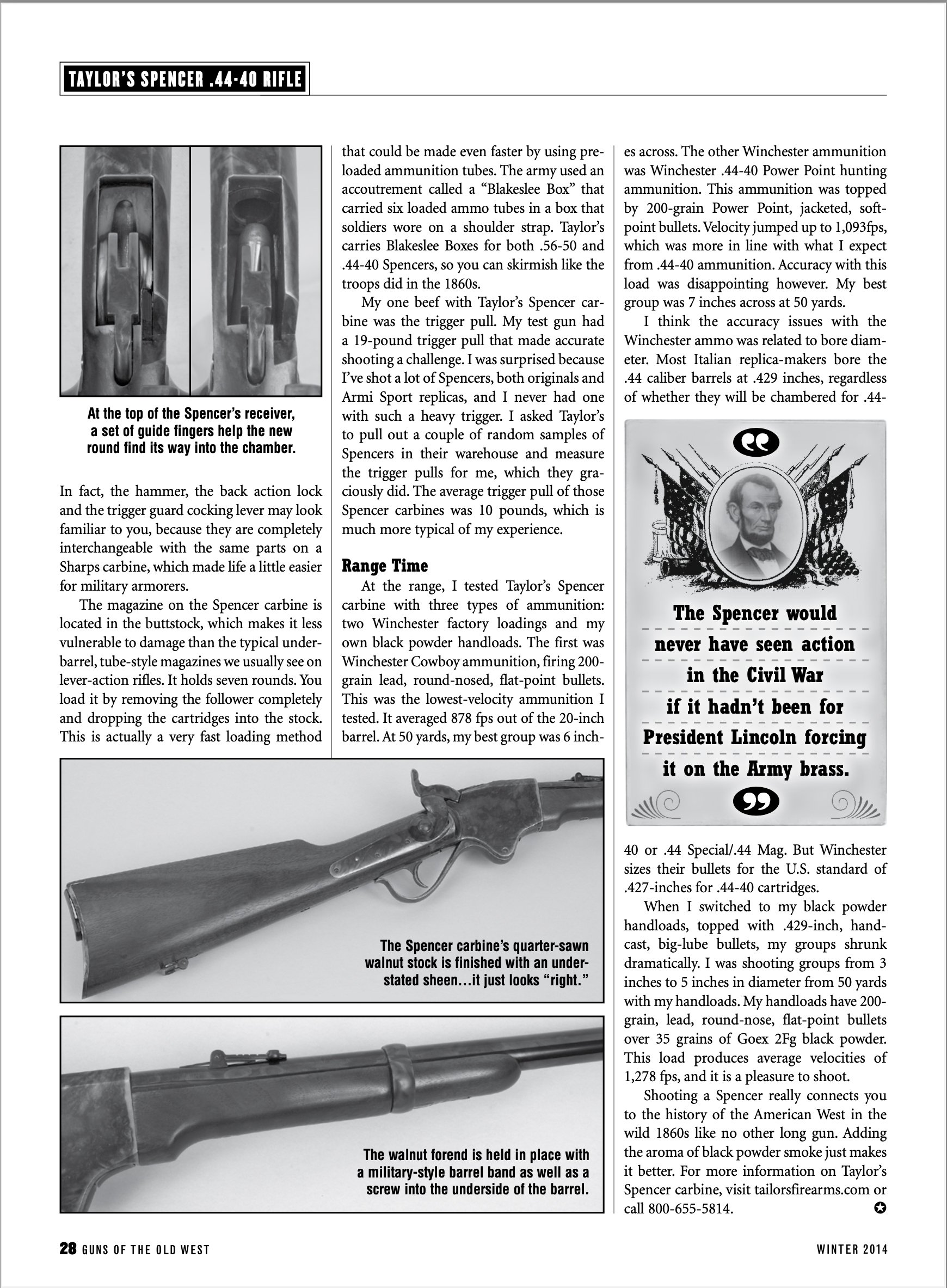

The forearm is secured to the round 20-inch barrel by a color case hardened, military style barrel band as well as by a screw into the bottom of the barrel. The barrel itself is polished to a high gloss, and it is finished in a dark blue. The front sight is a fixed blade of the type commonly seen on nineteenth century military arms. The rear sight is dovetailed into the barrel, allowing it to be drifted for windage adjustments. The sight itself is a well-made military sight. The base of the sight is a fixed battle sight with a very fine notch that has been nominally calibrated for 100 yards…very nominally, as it turned out.

The rear sight has a flip-up ladder for long range shooting. The base of the ladder is a fixed 200-yard sight. Above that is the sliding blade that is calibrated from 300 yards to 800 yards. The top edge of the ladder is notched to provide another fixed sight blade that is calibrated for a wildly optimistic 900 yards.

The 100-yard sight blade has two useable positions. There is a very fine notch, of the type that was so beloved by nineteenth century shooters, whose eyes must have been much better than mine. It is hard to see the sight picture with this sight, but when I did pull it together I was able to shoot pretty decent groups. I found that this fine sight notch was right on at 25 yards with all the ammo I tested. The second sighting method was to use the whole rear blade as a shallow, semi-buckhorn sight. This is basically the battle sight, and it is much easier to see the sight picture than with the fine notch. I was on target at about 50 yards shooting this way. To do real 100 yard shooting, I needed to use either the 200 yard or 300 yard sight positions, depending of the velocity of the ammunition I was shooting.

All of the metal on the Spencer carbine, south of the barrel, is color case hardened. The colors are muted dark blue over smoky amber. It looks great. Most of the carbine’s nine-pound weight is concentrated in the receiver with contains the massive rolling block action. This action is very simple and very robust. When you compare it to the much more delicate Winchester toggle link design, you can see why it appealed to the military. The action is basically one moving part. A big semi-circular breechblock swings down to expose the section machined to accept the cartridge from the magazine. Racking the lever back up swings the breechblock up to feed the cartridge into the chamber, ready to fire.

Unlike on a Winchester, working the lever only feeds and ejects cartridges. It does not cock the hammer. That is something you need to do manually. The hammer is massive, and it is easily manipulated to fire. In fact, the hammer, the back action lock, and the trigger guard cocking lever may look familiar to you, because they are completely interchangeable with the same parts on a Sharps carbine, which made live a little easier for military armorers.

The magazine on the Spencer carbine is located in the butt stock, which makes it much less vulnerable to damage than the typical under-barrel tube style magazines we usually see on lever action rifles. It holds seven rounds. You load it by removing the follower completely and dropping the cartridges into the stock. This is actually a very fast loading method that could be made even faster by using pre-loaded ammunition tubes. The army used an accoutrement called a Blakeslee Box that carried six loaded ammo tubes in a box that soldiers wore on a shoulder strap. Taylor’s carries Blakeslee Boxes for both 56-50 and .44-40 Spencers, so you can skirmish like the troops did in the 1860s.

My one beef with Taylor’s Spencer carbine was the trigger pull. My test gun had a 19-pound trigger pull that made accurate shooting a challenge. I was surprised because I’ve shot a lot of Spencers, both originals and Armi Sport replicas, and I never had one with such a heavy trigger. I asked Taylor’s to pull out a couple of random samples of Spencers in their warehouse and measure the trigger pulls for me, which they graciously did. The average trigger pull of those Spencer carbines was 10 pounds, which is much more typical of my experience.

At the range I tested Taylor’s Spencer carbine with three types of ammunition, two Winchester factory loadings, and my own black powder handloads. The first was Winchester Cowboy ammunition, firing a 200-grain lead round nosed flat point bullets. This was the lowest velocity ammunition I tested. It averaged 878 feet per second out of the 20-inch barrel. At 50 yards, my best group was six inches across. The other Winchester ammunition was their Winchester .44-40 Power Point hunting ammunition. This ammo was topped by 200-grain Power Point, jacketed soft point bullets. Velocity jumped up to 1,093 feet per second, which was more in line with what I expect from .44-40 ammunition. Accuracy with this load was disappointing. My best group was seven inches across at 50 yards.

I think the accuracy issues with the Winchester ammo was related to bore diameter. Most Italian replica makers bore the .44 caliber barrels at .429 inches, regardless of whether they will be chambered for .44-40 or .44 Spl/.44 Magnum. But Winchester sizes their bullets for the U.S. standard of .427-inches for .44-40 cartridges.

When I switched to my black powder handloads, topped with .429-inch, hand cast big lube bullets, my groups shrunk dramatically. I was shooting groups from three-inches to five inches in diameter from 50 yards with my handloads. My handloads have 200-grain, lead, RNFP bullets over 35 grains of Goex 2Fg black powder. This load produces average velocities of 1,127.8 fps, and it is a pleasure to shoot.

Shooting a Spencer really connects you to the history of the American west in the wild 1860s like no other long gun. Adding the aroma of black powder smoke just makes it better.

SPECIFICATIONS:

Taylor’s Spencer carbine

CALIBER: .44-40 (tested), .45 Colt, .56-50

BARREL: 20 inches

OA LENGTH: 37 inches

WEIGHT: 9 lbs

STOCK/GRIPS: Walnut

SIGHTS: Rear ladder sight, Front military blade sight

ACTION: Rolling block lever action

FINISH: Color case hardened receiver, hammer and lever, balance blued

CAPACITY: Seven

MSRP: $1,623

Point of Contact:

Taylor’s & Company, Inc.,

304 Lenoir Dr,

Winchester, VA 22603

800-655-5814