Shooting Paper Cartridges In Cap & Ball Revolvers

Shoot historically correct paper cartridges in your revolvers.

Thanks to John Gurnee, one of our readers, this weekend I was shooting cap and ball revolvers the same way our ancestors did; with combustible paper cartridges. Most of us who shoot cap and ball sixguns load them up with loose powder and ball. But that was rarely the way people in the nineteenth century loaded them. They used cartridges.

We tend to think of cartridges as being exclusively made of metallic cartridge cases holding the primer, powder and bullet together in a single convenient, durable unit. But cartridges are much older than that. Musket cartridges were in fairly general use by the 1590s. Those cartridges were a whole different animal from the cartridges we have today. They contained powder and a musket ball wrapped in a greased, paper tube. You tore the end off of the paper and poured the powder down your musket. Then you rammed the ball on top of the powder and you held the charge in place by ramming the cartridge paper down the bore as a wad.

That was pretty much the state of the art for cartridges from the 1590s until the 1840s. But the development of Colt’s revolving pistols pushed cartridges in a whole new direction. The speed with which you could empty on of Col. Colt’s revolvers was lightning fast, but the speed at which that revolver could be reloaded with loose powder and ball was glacial. People started looking for a better way. That’s when cartridges changed from a convenient container for a single charge of powder and ball into a complete, fireable unit that would leave no ash behind to get in the way of reloading.

As a concept, it took off. In no time revolver cartridges were being made out of a variety of materials. The most popular were made of nitrated paper, foil or gut. Gut cartridges are the most interesting to me. These were made like sausage casings using lambs’ intestines. They were dried on forms, then filled with powder and a bullet and given a light coat of shellac. They had the virtue of being waterproof, but they were delicate. When you rammed them into a revolver chamber, the gut casing broke apart, exposing the powder to fire from the cap. Cartridges made of thin metal foil were also waterproof, but you had to either tear the bottom of the cartridge before loading or prick it through the nipple after loading , or the foil would stop the fire from the cap from igniting the powder.

The most common material for cartridges was nitrated paper. This is paper soaked in a potassium nitrate solution and allowed to dry. It burns easily and completely. Cartridges made from nitrated paper are not water repellent, nor are they particularly rugged. They will stand up to some handling, but not much. In the nineteenth century they were shipped sold in stout packaging, and that is where they stayed until the time came to load them in a gun.

Either women or children made most cartridges in the nineteenth century. Making paper cartridges is fairly exacting work, and full-grown men weren’t considered nimble enough to do it well. As a full-grown man who has made my share of combustible cartridges, I can vouch for that. That’s why so few people shoot them these days.

Given all that, out of the blue we were contacted by one of our readers, John Gurnee, who wanted to know if we would like to try out some of his combustible cartridges. Not being one to turn down free ammo, I said yes, though I have to admit that I wasn’t expecting them to be anything special. I was wrong.

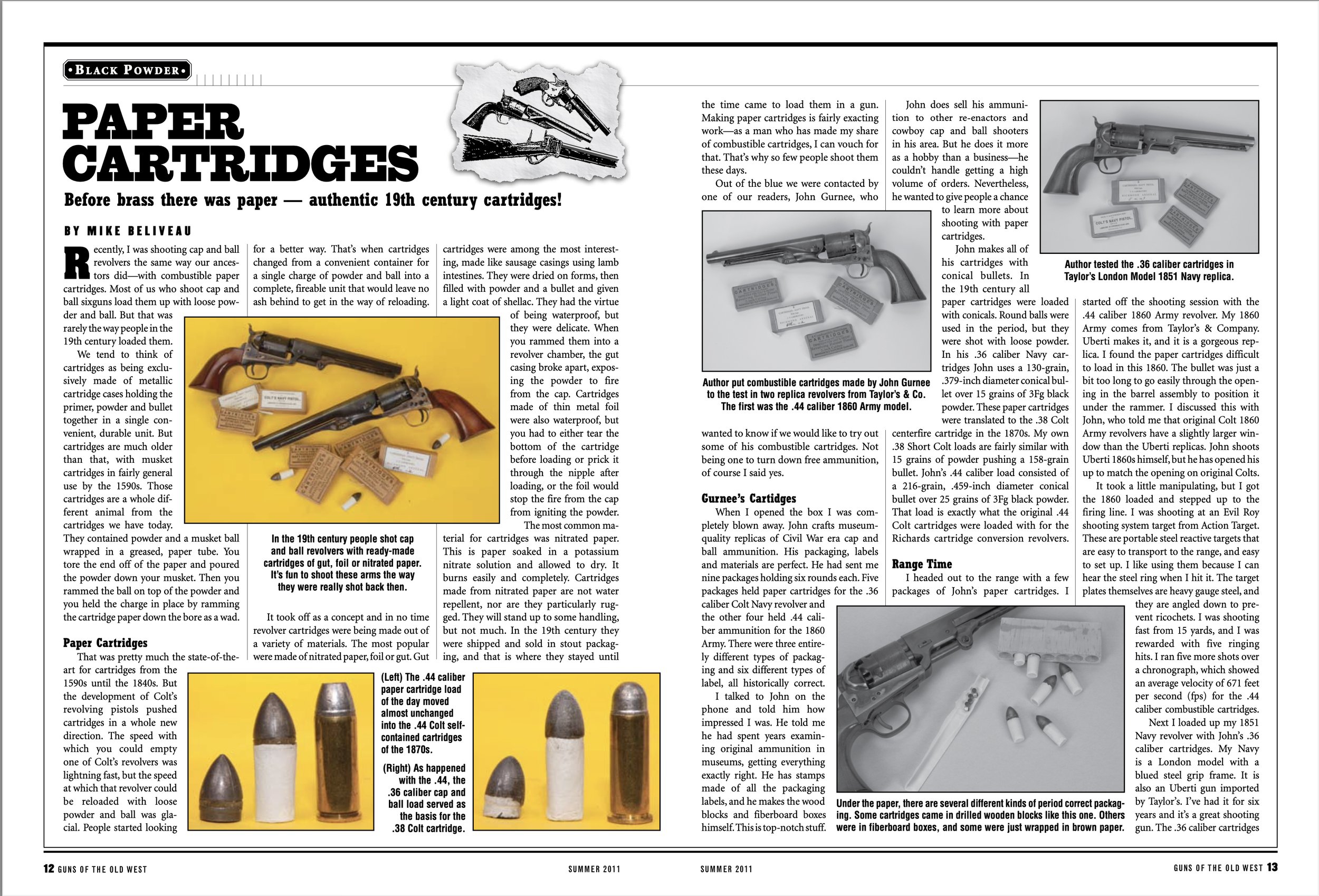

When I opened the box I was completely blown away. John crafts museum quality replicas of Civil War era cap and ball ammunition. His packaging, labels, materials…everything …is perfect. He had sent me nine packages holding six rounds each. Five packages held paper cartridges for the .36 caliber Colt Navy revolver and the other four held .44 caliber ammo for the 1860 Army. There were three entirely different types of packaging and six different types of label; all historically correct.

I talked to John on the phone and told him how impressed I was. He told me he had spent years examining original ammunition in museums, getting everything exactly right. He has stamps made of all the packaging labels, and he makes the wood blocks and fiberboard boxes himself. This is top notch stuff.

John asked me not to reveal his contact information. He does sell his ammunition to other re-enactors and cowboy cap and ball shooters in his area. But he does it more as a hobby that a business. He couldn’t handle getting a high volume of orders from our readers. But he wanted to give people a chance to learn more about shooting with paper cartridges.

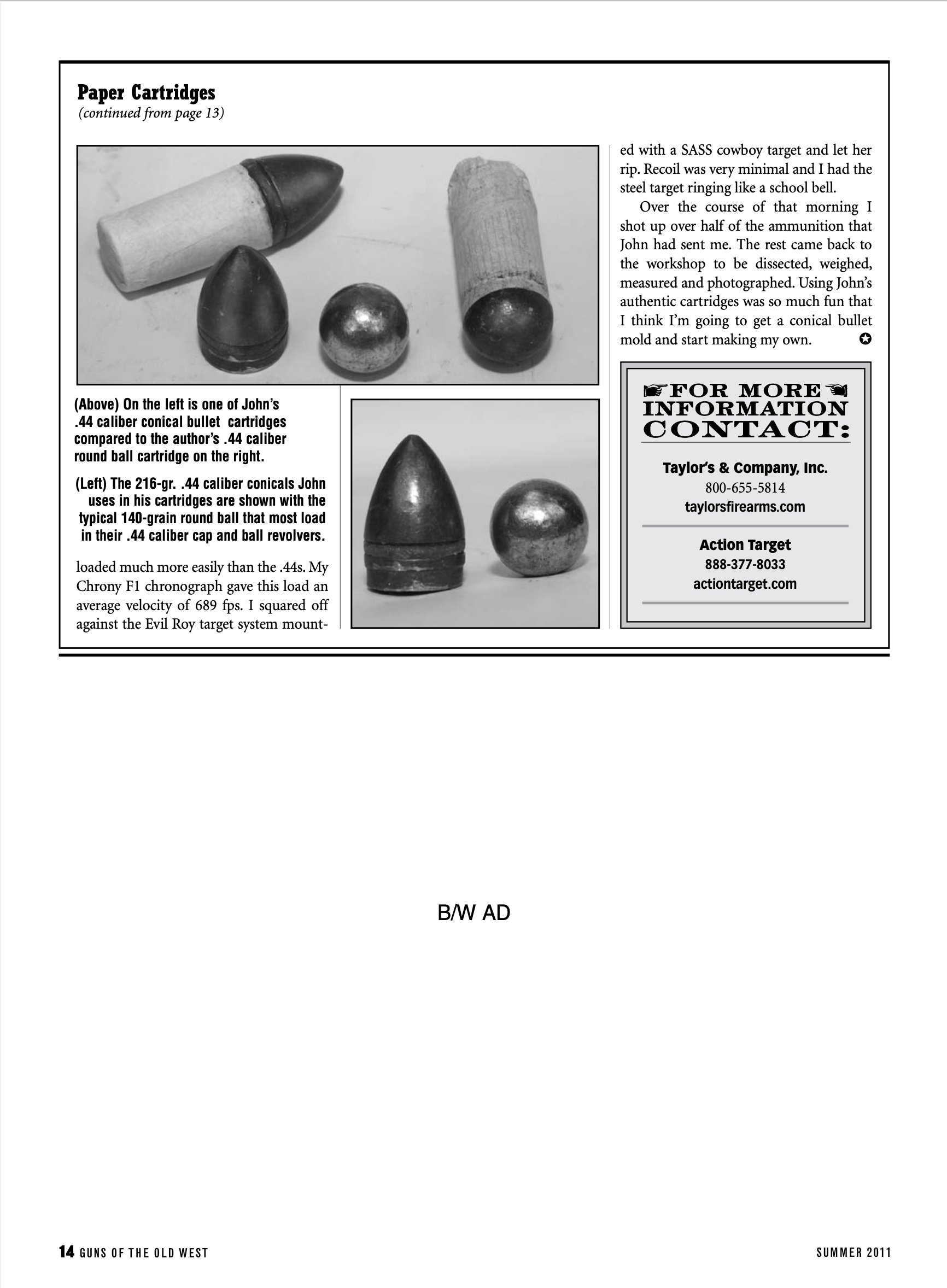

John makes all of his cartridges with conical bullets. In the nineteenth century all paper cartridges were loaded with conicals. Round balls were used in the period, but they were shot with loose powder. In his .36 caliber Navy cartridges John uses a 130-grain, .379-inch diameter conical bullet over 15 grains of 3Fg black powder. These paper cartridges were translated to the .38 Colt centerfire cartridge in the 1870s. My own .38 Short Colt loads are fairly similar with 15 grains of powder pushing a 158-grain bullet. John’s .44 caliber load consisted of a 216-grain, .459-inch diameter conical bullet over 25 grains of 3Fg black powder. That load is exactly what the original .44 Colt cartridges were loaded with for the Richards cartridge conversion revolvers.

I headed out to the range with a few packages of John’s paper cartridges. I started off the shooting session with the .44 caliber 1860 Army revolver. My 1860 Army comes from Taylor’s & Company in Winchester, Virginia. Uberti makes it, and it is a gorgeous replica. I found the paper cartridges difficult to load in this 1860. The bullet was just a bit too long to go easily through the opening in the barrel assembly to position it under the rammer. I discussed this with John who told me that original Colt 1860 Army revolvers have a slightly larger window than the Uberti replicas. John shoots Uberti 1860s himself, but he has opened his up to match the opening on original Colts.

It took a little manipulating, but I got the 1860 loaded and stepped up to the firing line. I was shooting at an Evil Roy shooting system target from Action Targets. These are portable steel reactive targets that are easy to transport to the range, and easy to set up. I like using them because I can hear the steel ring when I hit it. The target plates themselves are heavy gauge steel, and they are angled down to prevent ricochets. I was shooting fast from 15 yards, and I was rewarded with five ringing hits. I ran five more shots over a chronograph, which showed an average velocity of 671 feet per second for the .44 caliber combustible cartridges.

Next I loaded up my 1851 Navy revolver with John’s .36 caliber cartridges. My Navy is a London model with a blued steel grip frame. It is also an Uberti gun imported by Taylor’s & Co. I’ve had it for six years and it’s a great shooting gun. The .36 caliber cartridges loaded much more easily than the .44s. My Chrony F1 chronograph gave this load an average velocity of 689 feet per second. I squared off against the Evil Roy target system mounted with a SASS cowboy target and let her rip. Recoil was very minimal and I had the steel target ringing like a school bell.

Over the course of that morning I shot up over half of the ammo that John had sent me. The rest came back to the workshop to be dissected, weighed, measured and photographed. Using John’s authentic cartridges was so much fun that I think I’m going to get a conical bullet mold and start making my own.

Points of contact:

Taylor’s & Company, Inc.

304 Lenoir Drive

Winchester, VA 22603

800-655-5814