Smoothbore Shootout

Flintlock smoothbores are more accurate than most people think.

Smooth bores were the workhorse guns on the colonial American frontier. For warfare, or for hunting, they dominated the American firearms scene for most of the eighteenth century. But, as the frontier moved to the open spaces of the Great Plains in the nineteenth century, big bore rifles, with their ability to accurately hit big game at long distances, became the became the standard guns of frontiersmen.

For a time, smoothbore muskets maintained their pre-eminence on the battlefield because they had much higher rates of fire than slower loading muzzleloading rifles. But in 1849, the invention of the rifled musket, firing a Minie ball, erased that advantage.

The Minie ball was an undersized, hollow-based bullet. Because it was undersized, it could be loaded as quickly as a smooth bore musket ball, but, upon firing, the hollow base expanded to engage the barrel’s rifling, allowing accurate, long range fire.

So, by the mid-nineteenth century, smooth bored guns were relegated to hunting small game and birds. And, as time passed, knowledge of of the actual capabilities of flintlock was lost as the generation that used them last passed on to their Celestial reward..

By the time of the muzzleloading renaissance in the mid-twentieth century, the consensus was that smooth bored muskets were so inaccurate, they couldn’t hit a barn from the inside. The conventional wisdom for military muskets like the Brown Bess was that they were worthless for shooting at individual soldiers. It was widely believed that the value of the musket was in its high rate of fire when directed at massed groups of infantry, and that the deadliest part of the Brown Bess was really the bayonet.

Lately, smooth bored guns have become more popular in the muzzleloading community, and most Muzzle Loading Rifle Association matches feature “Trade Gun” events, specifically for traditional smooth bored guns with no rear sight. But, today’s Trade Gun competitors do not load their guns the way our eighteenth-century forbearers did. Instead, they load smooth bores exactly the same way muzzleloading rifles are loaded, which is with patched round balls. They are convinced that this is the only way to get acceptable accuracy.

Today’s muzzleloading shooters have completely bought into the story that traditionally loaded smooth bores are wildly inaccurate. But that belief fails the logic test.

If smoothbores were that inaccurate, people would have kept on shooting longbows and crossbows. Certainly, Europeans would not have adopted smooth bored guns as hunting weapons if they weren’t accurate enough to routinely take game. Likewise, if military muskets were only viable for volley fire against massed targets, they would not have become the dominant battlefield weapon.

In fact, here in America, during most of the wars of the eighteenth century, massed infantry battles, fought across open fields were the exception rather than the rule. During the French and Indian war, fights were more like the Battle of the Monongahela, where Braddock was defeated. The fights took place in dense woodland, where volley fire was useless.

Braddock lead about 1,300 picked troops into the Battle of the Monongahela. He suffered 68% casualties, with over 400 soldiers killed outright. For the most part, those casualties were meted out by native Americans shooting smooth bored muskets.

A generation later, after Paul Revere’s midnight ride. The 1,500-man British Army detachment that descended on Concord and Lexington, took 300 casualties during their retreat back to Boston. Those losses were caused by the smooth bored muskets and fowling pieces wielded by American militia.

And, consider this, at the battle of Blue Licks, Kentucky in 1782, Daniel Boone armed himself with a smooth bored fowling piece. There is no question that Boone knew his way around a rifle, but he obviously considered the fast loading capability of smooth bores to be an important factor for that fight. I doubt that an experienced fighter like Boone would go up against a force of Shawnee warriors using a weapon that wouldn’t hit what he aimed at. Yet, he left his rifle behind, in favor of a smooth bore.

By saying this, I’m not claiming that a smooth bored flintlock is precision shooting machine, far from it. What I am saying is that it is accurate enough.

In the eighteenth century, the British army considered 150 yards to be the maximum practical range for the Brown Bess. The army’s standard for accuracy at 150 yards was to hit a target six feet tall by four feet wide with 50% of the rounds fired. That certainly isn’t stellar accuracy in anyone’s book. But, point blank range for the Bess was considered to be 80 yards, and, at that range 100% of shots fired were expected to hit a man-sized target. Most people today do not believe a smooth bore is capable of that kind of accuracy.

I decided to see if my smoothbores could deliver the level of practical accuracy expected by the British Army.

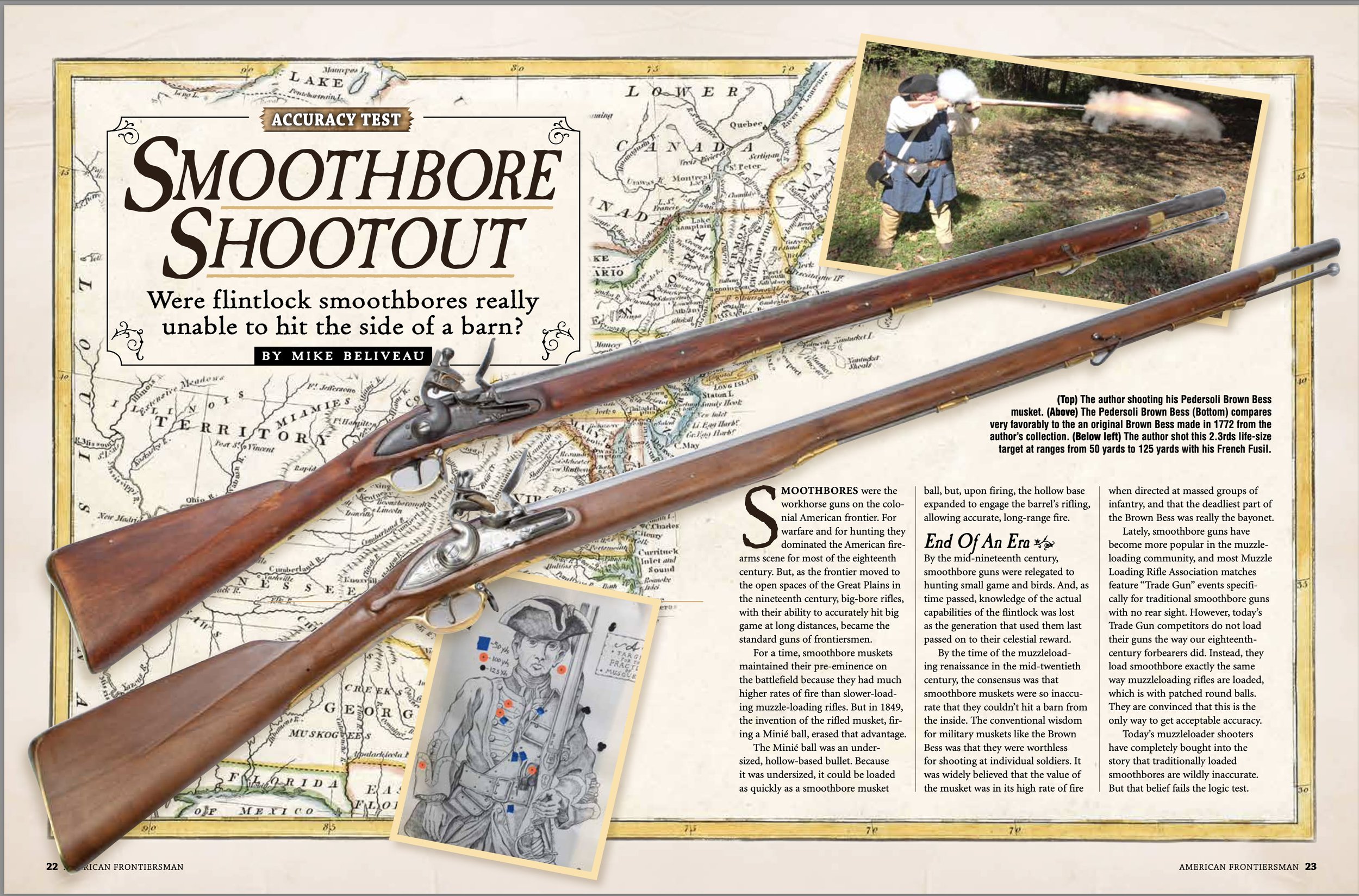

For the test, I selected two guns. To represent civilian militia arms, I selected my 20 GA French Fusil DeChasse, built by Shawn Webster. And, for the military test, I decided to use a Brown Bess musket made by Davide Pedersoli in Italy, and imported by Dixie Gun Works in Union City, Tennessee.

Pedersoli’s Brown Bess replica, is essentially a 1769 short land pattern musket. So, it is not really period correct for the French & Indian War era. But it is perfectly fine for the Revolutionary War. There are a couple of bothersome issues that detract from the historical accuracy of Pedersoli’s Bess. First, the lock is incorrectly marked “Grice 1762”. By this model of Bess, makers were no longer signing and dating their locks. But, overall, Pedersoli’s Bess compares favorably with an original 1770s vintage Brown Bess in my collection.

I wanted to load the Bess for the test with the same load British soldiers would have used during the eighteenth century. To find the proper load, I consulted “The British Gunner” by J. Morton Spearman. This book first appeared in 1828, and it is basically the ordnance officer’s manual for the British Army. It lists the 1775 paper cartridge load for the Brown Bess as a .69 caliber round ball and six drams of powder.

A dram weights 27.34 grains, so that six-dram load is a whopping 165 grains of musket powder. That is a wicked lot of powder. Even accounting for the priming, that is still at least 150 grains of gunpowder down the bore.

Spearman cautions that modern (meaning 19th century) gunpowder was stronger than the powder they had in 1775, and that the load should be dropped by up to 25% with nineteenth century powder. But what does that mean in terms of today’s powder?

Today, only Swiss brand black powder equals the potency of nineteenth century black powder. I decided that I could safely use the original eighteenth century load if I used 1Fg Goex. So, I made up paper cartridges that were each loaded with a .69 caliber round ball and 165 grains of Goex 1Fg black powder.

To make the cartridges I bought a Brown Bess paper cartridge kit from the Jefferson Arsenal. This kit comes with all the materials needed to make 80 Brown Bess cartridges. Once you have the kit, it is easy to replenish papers and balls to keep making cartridges.

I could have used standard B-27 silhouettes for targets, but that would have dampened my eighteenth-century vibe. A couple of years ago I bought some targets that are two-thirds size renditions of eighteenth-century soldiers. I thought that they would be perfect for this experiment. I wanted to test the performance of the Brown Bess first at the 80-yard point blank distance, then at 100 yards, and finally at the maximum range of 150 yards. Because the targets were only two-thirds of life size, I decided to shoot at 50 yards, 75 yards and 100 yards to provide the proper proportional distances.

I loaded the Brown Bess in typical military fashion. I bit the end off of the paper cartridge and filled the priming pan with 1Fg powder right from the cartridge. Then I closed the frizzen, and poured the remaining powder down the bore. After that, the empty paper cartridge, with the ball still contained in the paper, is pushed into the bore, and seated on the powder with the ramrod. At that point, the Brown Bess is primed, loaded, and ready to fire.

I shot five rounds at the target at each distance, and I cleaned the bore between each five-shot string. As it turned out, only four shots actually hit the target out of each string. I’m assuming that the first shot out of a clean bore. Is being thrown wild, but I’ll need to do some additional testing to confirm that.

The good news is that the four shots out of each string that actually hit the target, delivered results that very closely matched the level of marksman expected by the British Army.

At fifty yards (80 yard equivalent), the Brown Bess delivered four solid hits, any one of which would have taken an opposing soldier out of the fight. At 75 yards, I put three out of four shots into the opposing soldier. The fourth shot only missed the target by half an inch. When I moved the target back to 100 yards (150-yard equivalent) I only managed to land two shots on the soldier, but that’s still better shooting than the British army expected out of its soldiers. So, on the whole I was quite happy with the Bess’ performance

Next, I shot the fusil. Guns like this, some made in the colonies themselves, others imported from England, Belgium, France and Spain, were the main arms of both the century.

Today, most smoothbore shooters use a patched ball, exactly as they would load a rifle, but there is no evidence that this was done with smoothbores in the eighteenth century. During that time smoothbores were loaded with a naked, slightly undersized ball, and the ball was held in place with a wad.

All sorts of materials were used as wads, from wasp’s nest to felt. The favored wad materials were either cut paper or tow, which is a coarse fiber by-product of linen making. Unfortunately, I have found tow, and to a lesser extent, paper to be fire hazards after they leave the muzzle and land in the dry leaf litter of the forest floor. So, now I use a small peice of pure wool blanket material as wadding.

My load for the fusil is 110 grains of 2Fg Swiss black powder, under a bare .610-inch diameter soft lead ball. The ball is kept in place by a one-inch square piece of wool blanket, which is rammed solidly on top of the ball.

I carry my balls, wads and tools in a copy I made of the bag Lemuel Lyman carried at the battle of Lake George in 1755. This bag is typical of the type of shot bag routinely used during the French and Indian War. It is a simple D-shaped bag that is divided into two internal pockets by a welt. In the back pocket I carry essential tools and cleaning supplies, along with a few extra flints. The front pocket is reserved for ammo. I dump loose balls directly into the Lyman bag, along with a supply of loose wads.

When I need to load, powder from the horn is measured out, and poured down the bore. Then I reach into the Lyman bag and grab a loose ball and a wad. I drop the ball into the barrel, push a wad in on top of it, and ram them both down on the powder with the ramrod. Then I prime out of the powder horn, and I’m ready to fire. It provides a very fast reload. Not quite as fast as a paper cartridge, but much faster than loading a rifle.

I conducted a similar test with the fusil as I had with the Brown Bess. I used a similar 2/3rds life-size paper target, but my distances for the fusil were 50 yards (80-yard equivalent), 100 yards (150-yard equivalent) and 125 yards (180-yard equivalent). The results were eye-opening.

Once again, at 50 yards, I drilled the target, landing all five shots on the soldier. At 100 yards I landed three killing shots, one wounding shot in the arm, and the fifth shot missed his head by barely two inches. I shot so well at 100 yards that I got cocky, and moved the target out to 125 yards. That was my undoing. I missed the soldier with all five shots, though I came close enough to scare him.

This experiment proved to me that smooth bored gun, whether they are military muskets, or civilian guns, are capable of consistent killing accuracy as long as shots are kept inside 150 yards. If you need to hit targets farther away than that, you’re in rifle country.

Points of Contact:

Dixie Gun Works, Inc.

1412 West Reelfoot Ave

Union City, TN 38281

800-238-6785

https://www.dixiegunworks.com/

Shawn Webster

280 W 400 S

St George Utah 84770

The Jefferson Arsenal

TheJeffersonArsenal@hotmail.com

(240) 409-2566