Handloading on the go

Portable reloading tools that go where you go.

These days I do most of my reloading on progressive presses and turret presses. In my shop I have two dedicated reloading benches with four, bench-mounted reloading presses. But that wasn’t always the case. When I first started reloading, over 20 years ago, I was living in a small rental property that had no room for a dedicated reloading bench. But I was shooting a lot, and there was no way I could feed that habit at the cost of factory ammunition. My solution was to forget the bench, and use portable handloading equipment.

Space limitations are just one reason for using portable reloading equipment. Even though I have a great bench set up, I still use the Lee Hand Press that I bought all those years ago. In my case, I like to use it at the rifle range while I’m working up a new load for black powder, single shot rifles. With some of those obsolete cartridges, brass cartridge cases can cost upwards of five dollars each. At those prices I’m not going to buy 100 pieces of brass. Usually I’ll get 10 or 20 pieces of brass to start with. After putting together a baseline test load at home, I can fine-tune it right at the range by reloading my fired cases using the hand press while sitting at the bench rest table.

There are lots of reasons for portable reloading equipment. Whether you work for long periods of time out of remote camps, or if you commute to warmer climes for the winter, or travel to a campground for the weekends, it may not be worth the expense and the trouble of recreating your full-blown reloading set-up at your satellite location. That’s where portable handloading equipment can save the day.

Portable reloading equipment came on the scene with the first centerfire rifle cartridges in the late 1860s. In the early days, rifle manufacturers often included a bullet mold and a tong-style reloading tool as part of the package. Buffalo hunters in particular insisted that their rifles come with these implements. Usually the hide hunters would take to the field with a few hundred store-bought cartridges and a wagon loaded with 25-pound kegs of black powder, along with as much lead as they could transport. Each evening, while the other men did camp chores, the buffalo hunter would cast bullets, and reload the cartridges expended in that day’s hunt.

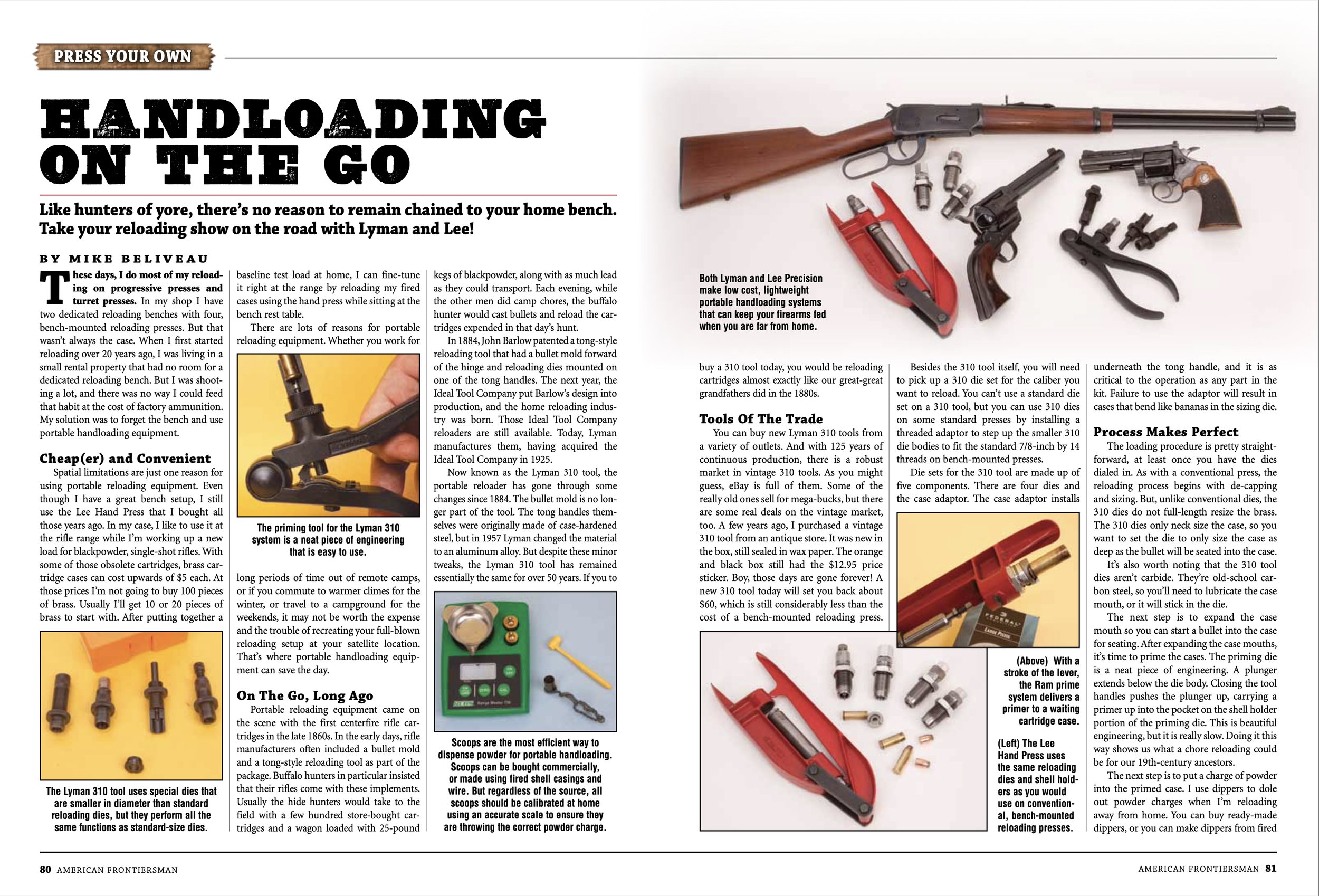

In 1884 John Barlow patented a tong-style reloading tool that had a bullet mold forward of the hinge, and reloading dies mounted on one of the tong handles. The next year the Ideal Tool Company put Barlow’s design into production, and the home reloading industry was born. Those Ideal Tool Company reloaders are still available. Today Lyman manufactures them, having acquired the Ideal Tool Company in 1925.

Now known as the Lyman 310 tool, the portable reloader has gone through some changes since 1884. The bullet mold is no longer part of the tool. The tong handles themselves were originally made of case hardened steel, but in 1957 Lyman changed the material to an aluminum alloy. But, with just minor tweaks, the Lyman 310 tool has remained essentially the same for over 50 years. If you by a 310 tool today, you will be reloading cartridges almost exactly like our great-great grandfathers did in the 1880s.

You can buy new Lyman 310 tools from a variety of outlets. And with 125 years of continuous production, there is a robust market in vintage 310 tools. As you might guess, eBay is full of them. Some of the really old ones sell for mega-bucks, but there are some real deals on the vintage market too. A few of years ago I purchased a vintage 310 tool from an antique store. It was new in the box; still sealed in wax paper. The orange and black box still had the $12.95 price sticker. Boy, those days are gone forever. A new 310 tool today will set you back about $60, which is still considerably less than the cost of a bench mounted reloading press.

Besides the 310 tool itself you will need to pick up a 310 die set for the caliber you want to reload. You can’t use a standard die set on a 310 tool, but you can use 310 dies on some standard presses by installing a threaded adaptor to step up the smaller 310 die bodies to fit the standard 7/8-inch by 14 threads on bench mounted presses.

Die sets for the 310 tool are made up of five components. There are four dies and the case adaptor. The case adaptor installs underneath the tong handle, and it is as critical to the operation as any part in the kit. Failure to use the adaptor will result in cases that bend like bananas in the sizing die.

The loading procedure is pretty straight forward, once you have the dies dialed in. As with a conventional press, the reloading process begins with de-capping and sizing. But, unlike conventional dies, the 310 dies do not full-length re-size the brass. The 310 dies only neck size the case, so you want to set the die to only size the case as deep as the bullet will be seated into the case. The 310 tool dies aren’t carbide. They’re old-school, carbon steel, so you’ll need to lubricate the case mouth, or it will stick in the die.

The next step is to expand the case mouth so you can start a bullet into the case for seating. After expanding the case mouths, it’s time to prime the cases. The priming die is a neat piece of engineering. A plunger extends below the die body. Closing the tool handles pushes the plunger up, carrying a primer up into the pocket on the shell holder portion of the priming die. This is beautiful engineering. But it is really slow. Doing it this way shows us what a chore reloading could be for our nineteenth century ancestors.

The next step is to put a charge of powder into the primed case. I use dippers to dole out powder charges when I’m reloading away from home. You can buy ready-made dippers, or you can make dippers from fired cartridge cases, by wrapping them with wire to make a handle. But, whether you buy dippers or make your own, it is important to ensure they are throwing the correct charge. Commercial dipper sets come with a chart telling you how much powder each dipper holds for a wide range of powders. In my experience, those charts are not to be trusted. Regardless of whether they are commercial or homemade, I always weigh the charges from my scoops on a good reloading scale. If necessary, I’ll file down the mouths of my dippers until they hold the correct charge of powder, as verified by my scale.

The final step is to screw the seating die into the handles and seat and crimp the bullet. Obviously this procedure takes significantly longer to load a box of ammo than a progressive press, but a progressive press weighs about 30 pounds, not counting the bench it needs to be mounted on. In contrast the whole 310 reloading outfit weighs about a pound…something to think about when you’re packing into a remote location.

I have a couple of die sets for my 310 tool, but over the years the one I’ve used the most is the .38 Spl set. For a long time my lightweight, go anywhere, gun was a .38 Spl Colt Diamondback revolver. This gun looks like Colt’s famous Python .357, but it was built on Colt’s .22 caliber “D” frame. With it’s four-inch barrel, the Diamondback is very light to carry on a hike, and, in .38 Spl, it provided all the gun I needed while hiking and camping, as long as I wasn’t in bear country.

On the 310 tool, I load .38 Specials with a hard-cast 158-grain lead bullet over 3.5 grains of Hodgdon’s HP-38 powder. I scoop the powder with a .5cc Lee dipper that I cut down to hold 3.5 grains. This load averages 805 feet per second from the four-inch barrel of the Diamondback. Loads from the 310 tool are as accurate as the rounds from my bench mounted press. From the 25-yard bench this load usually turns in one-inch to one and half-inch groups.

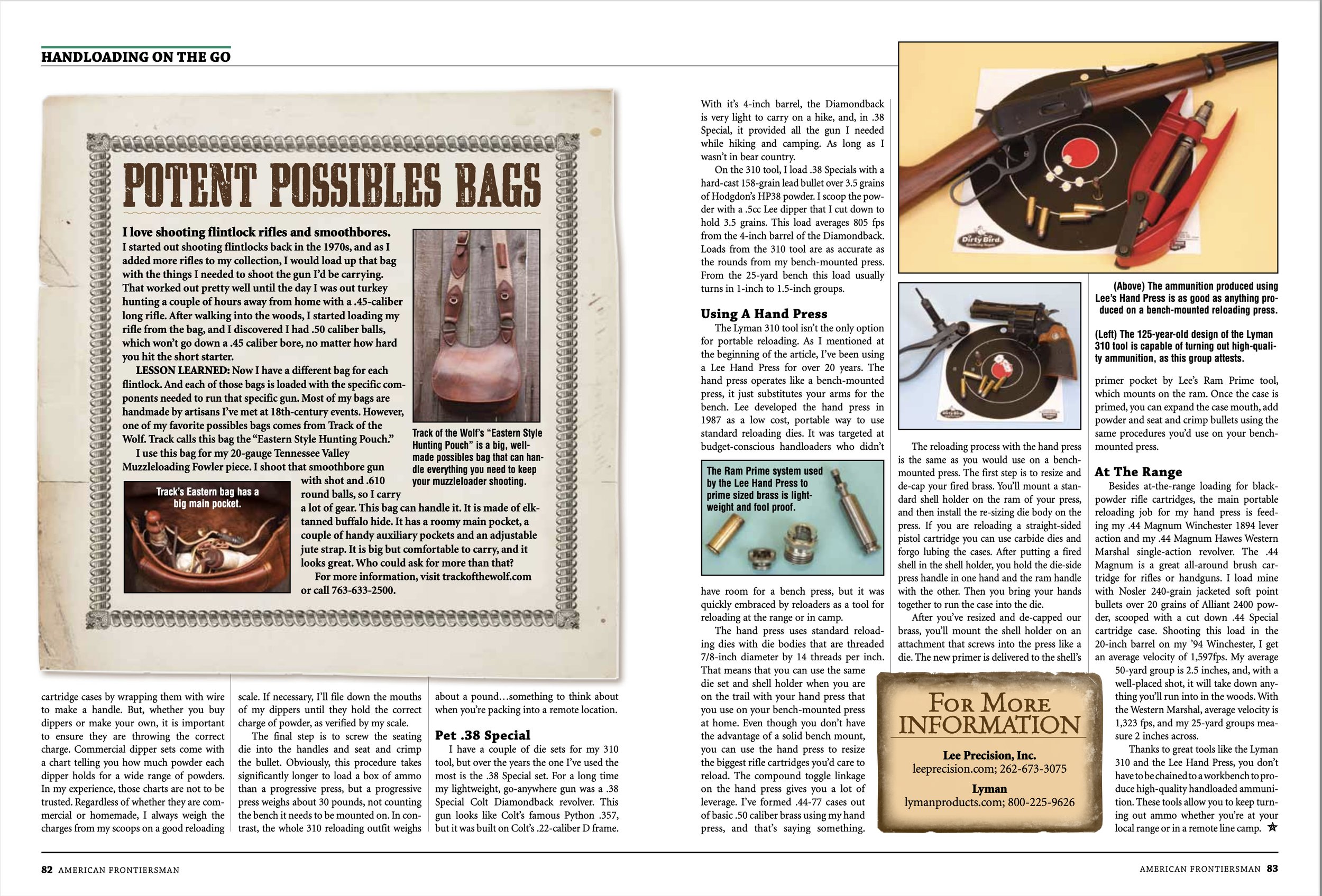

The Lyman 310 tool isn’t the only option for portable reloading. As I mentioned at the beginning of the article, I’ve been using a Lee Hand Press for over 20 years. The Hand Press operates like a bench-mounted press, it just substitutes your arms for the bench. Lee developed the hand press in 1987 as a low cost, portable way to use standard reloading dies. It was targeted at budget conscious handloaders who didn’t have room for a bench press. But it was quickly embraced by reloaders as a tool for reloading at the range or in camp.

The Hand Press uses standard reloading dies with die bodies that are threaded 7/8-inch diameter by 14 threads per inch. That means that you can use the same die set and shell holder when you are on the trail with your Hand Press that you use on your bench-mounted press at home. Even though you don’t have the advantage of a solid bench mount, you can use the hand press to resize the biggest rifle cartridges you’d care to reload. The compound toggle linkage on the hand press gives you a lot of leverage. I’ve formed .44-77 cases out of basic .50 caliber brass using my hand press, and that’s saying something.

The reloading process with the Hand Press is the same as you would use on a bench-mounted press. The first step is to re-size and de-cap your fired brass. You’ll mount a standard shell holder on the ram of your press, and install the re-sizing die body on the press. If you are reloading a straight-sided pistol cartridge you can use carbide dies and forgo lubing the cases. After putting a fired shell in the shell holder, you hold the die-side press handle in one hand, and you hold the ram handle in your other hand. Then you bring your hands together to run the case into the die.

After you’ve re-sized and de-capped our brass, you’ll mount the shell holder on an attachment that screws into the press like a die, the new primer is delivered to the shell’s primer pocket by Lee’s Ram Prime tool, which mounts on the ram. Once the case is primed you can expand the case mouth, add powder and seat and crimp bullets using the same procedures you’d use on your bench-mounted press.

Besides at the range loading for black powder rifle cartridges, the main portable reloading job for my hand press is feeding my .44 Magnum Winchester 1894 lever action and my .44 Magnum Hawes Western Marshal single action revolver. The .44 Magnum is a great all around brush cartridge for rifles or handguns. I load mine with Nosler 240-grain jacketed soft point bullets over 20 grains of Alliant 2400 powder, scooped with a cut down .44 Spl cartridge case. Shooting this load in the 20-inch barrel on my ’94 Winchester, I get an average velocity of 1,597 feet per second. My average 50-yard group is two and a half inches, and, with a well-placed shot, it will take down anything you’ll run into in the woods. With the Western Marshal average velocity is 1,323 feet per second, and my 25-yard groups measure two-inches across.

Thanks to great tools like the Lyman 310 and the Lee Hand Press, you don’t have to be chained to a workbench to produce high quality, handloaded ammunition. These tools let keep turning out ammo whether you’re at your local range or in a remote line camp.

Points of contact:

Lyman Products Corporation

475 Smith Street

Middletown, CT 06457

800-225-9626

Lee Precision Inc.

4275 Highway U

Hartford, WI 53027

262-673-3075